By Lynda Covello

“You’ll never know just how much I miss you…”*

October 14, 2018. The world feels different today, too quiet, too fragile, too old. Too empty. The weather is turning seasonal at last; after weeks of indecision, it is definitively fall. Only yesterday it seemed like summer could last forever. Today it is clear: nothing does. Yesterday, I lost more than a dear friend. Yesterday I lost a healer and a soul-mate. Let me begin at the beginning, or what seems like the beginning, anyway.

In late 2007, I hit a wall. After two years of commuting to another city by air every week for work, two years of personal chaos, two years of unstable diabetes management, I was burnt out physically and emotionally. After 34 years of living well with T1D, pushing myself to achieve more, do more, BE more, than anyone ever expected of me, I just couldn’t do it anymore. I was diagnosed with severe depression. I took a medical leave on the strong encouragement of my healthcare team, and I went home to rest, recover, and try to hit the reset button on my health.

Six months earlier, we took in a five-month-old Siberian Husky who had been rejected by his first owner. Nobody seemed to know his name. We named him Arthur. I’m still not sure why. He answered to it almost as soon as we started calling him that. Arthur was stunningly beautiful – distinctive black, white and gray markings on a velvety soft coat, with the bluest eyes – but the best thing about him was his personality. He was sweet and cuddly and smart and full of humour and mischief. He washed himself like a cat, grooming his coat to a sparkling whiteness. We liked to say that he was intelligent, not obedient. He knew what you wanted him to do or not do, you could tell by the way he looked at you before deciding. He could be a handful.

Arthur really hated to be left alone, either in the house or out in the yard. He would howl and yip and cry out so that you would think someone was torturing him. In the first few years Arthur lived with us, we would arrive home after being out for even a couple of hours, to find notices from Animal Services that inspections were required in order to assess whether an animal was being mistreated in our home. When the officials would visit, Arthur would greet them enthusiastically at the door, and show them around the place. After seeing him, us, and the place where Art lived, they would leave, assuring us that we were providing him with proper care, and that nothing about him indicated he was being mistreated in any way. It was a severe case of separation anxiety, which we attributed to his being abandoned by his first owners. We ended up on a first-name basis with a lot of the officers, because it took about two years of practice before Arthur gained enough confidence to trust us to come home.

He was awful on a leash, pulling and jumping and darting around like a maniac, chasing squirrels, greeting people and other dogs, and just generally oblivious to the fact that he was dragging you hither and yon. He wasn’t house-trained, and despite how smart he was, he didn’t seem to care that we wanted him to go outside, not at his selected spots in the house.

He was demanding about food – he wanted what he wanted when he wanted it, and he was quite vocal about it. If you were eating something that he wanted, he would pester you until either you gave him some, or he had a chance to steal it from you.

In short, Arthur had all the traits that people warn you about in a Siberian Husky – high energy, anxious, stubborn and difficult to control. We were at our wit’s end trying to deal with him. The only thing that saved him was his charm, and the joyous way he encountered the world. And there was that great, expressive, handsome face of his, with the laughing eyes.

Then I came home sick, exhausted, defeated. I went to bed and basically stayed there for three weeks, and even after I started spending most of the day vertical, I was still clinically depressed. Something changed with Arthur. He stayed close to me every minute. He was sweet and affectionate, coaxing me into playing games with him. He started letting me know when he had to go outside, and became more consistent at not messing in the house. He waited patiently while I ate my food – I didn’t have much of an appetite – and stopped trying to steal it from me.

He coaxed me outside with him for walks, trotting back and forth between me and the door, making husky throat-song in soft encouragement until I got up and took him out. We started walking a little further each day, until we were up to a couple of hours. He still pulled on the leash, but not as much. He seemed to know how weak I was, and he adjusted for that. He wasn’t perfect, but he was much better. I started to get stronger, and to enjoy being outside exercising.

Arthur and I spent every day together for about 8 months while I was on med leave. During that time, he transformed from an unmanageable puppy to a well-mannered gentleman. It didn’t happen overnight, and there were things we continued to work on for a while, but generally, he became a very good family dog, and a pleasure to be around.

I also underwent a transformation. His joy infected me and I started to enjoy being in the world again. I took him with me when I ran errands – to the bank, the pharmacy, the bookstore – he was welcomed everywhere. People remembered his name before they remembered mine. He was a big dog who looked like a gray wolf – a really healthy, well-fed gray wolf with sparkling blue eyes – but he was gentle and affectionate with small dogs, children and people generally. And everyone loved the way he vocalized. He had something to say about everything.

Arthur saved me. He got me out of bed and out of the house and into the world again. He helped rebuild my physical strength by taking me out for daily walks. He introduced me to a whole new group of people – people with dogs – to replace the social connection that I lost when I left my job. He gave me a project to work on – refining his behaviours — when the work that I had done all my career was yanked out from under me. I need projects, I need work to do in order to feel fulfilled. Training Arthur became my new work, and he was a fully present collaborator in that work.

Arthur helped me to rebuild my mental health with his constant loving presence, his infectious joy in living in the moment, and his social and emotional intelligence. I was in pieces and he helped me to pick up the pieces and build a newer, stronger, better me, a me who could carry on in spite of the darkness, who could find way to be happy to live again. He helped me to understand and accept that while I could not fix everything that had led to my burn out, I could work at being better every day, one day at a time. I could find joy in the world again, in the simple daily living of my life. Arthur was my guru. He showed me a way to be in the world without trying so hard.

Now, in 2018, Arthur is almost twelve years old – which is old for a big dog. He has been slowing down in the past few months, showing the signs of age that a senior dog does: a certain stiffness in his joints, a lack of confidence for physically challenging activities like running up and down stairs or wrestling with his doggy friends. Two years ago we got him a puppy to keep him company. Jesse, an Alaskan Malamute who looks a lot like him, except for his eyes – his are blue, hers are brown – brought joy into his life (and ours) and gave him a real boost of energy and close companionship. She adores him, and they are inseparable. Lately, he’s been having trouble keeping up with Jesse on our walks, and our trail has been getting shorter.

We made some adjustments in his diet and exercise to account for his age, and last week, we added an anti-inflammatory medication that really helped. He has had a week of much easier walks, his movements fluid again and graceful. He has always been so graceful, moving like a dancer. He is up and ready to go every morning, greeting us with joy and anticipation.

On Saturday, we set off on a cool fall day for our morning walk. Arthur, Jesse, my husband and I stroll along the wooded trail that traces the ravine behind our home. Art’s feeling good and moving well, excited to be outside in the cool morning, tasting the air and sniffing all the smells of the earth and plants along the way. He is positively bouncy, and clearly enjoying himself. It’s hard to believe he’s almost 80 in human years.

There is a point along the trail where you can go down a steep hill into the park to our favourite off-leash enclosure. We haven’t gone down there in the past couple of weeks, as Arthur has been having trouble with the arthritis in his hips, and we’ve thought it would be too hard on him. Today, he is having none of that, and is off and heading down the hill to his favourite place, tugging at the leash. Jesse is ecstatic.

We have a lovely time at the off-leash, with a few old friends and a couple of new ones. Jesse is trying to play with every dog in the park, leaping and running and twirling in joy. Arthur is staying close to me and careful not to get bumped or jostled, but he is having fun interacting with dogs and people, with that crazy happy smile he has, vocalizing and cuddling with everyone. People always love Art, he is such a sweetheart. Eventually, we head back home, which means a walk back up that steep hill, but we take it slowly and he makes it, and then along the path back to our house.

We arrive home and do what we always do on Saturday mornings: have breakfast and sit down to rest from our walk before moving on to the rest of the day’s activities. The dogs settle in for their usual 6 or 7 hour nap, and the day proceeds. At 8:00 that evening, we all go out again, for our usual second walk of the day, and we do a good 30 minutes around the neighbourhood. Art’s still feeling good and moving well.

Sunday morning I wake up and go downstairs to the main floor, where Arthur has been sleeping for the past couple of months since he decided not to climb the stairs anymore. He is lying on his side, exactly as he was last night when I gave him his bedtime biscuit and said goodnight. He doesn’t get up. I encourage him, and I fill up his water bowl with fresh cool water. He gets up and drinks the whole bowl in one go.

I head back up to the kitchen to retrieve my phone and sunglasses for our morning walk. Jesse is already at the front door when I come back, but Art is laying down again. I can’t convince him to get up and ‘suit up’ in his harness for our walk. Jim comes down and talks to him enthusiastically about going outside, but he doesn’t move.

He never gets up again, although he tries many times in the next 7 or 8 hours. I stay in the room with him. At first, he’s just calm and breathing normally, but in the afternoon, his breathing becomes ragged, then laboured, and I think he might be in pain. I try massaging his back and legs, which has helped in the past, and he settles a bit. He tries to get up again, pushing up with his front legs and then trying to push up with his hinds, but he can’t quite make it. He collapses back to the ground and pants for a while from the exertion.

I pet him and brush his coat and I talk to him in tones of love and reassurance. Jesse comes down from upstairs and tries to engage him with a toy that they both love. Normally, there would be a very nuanced game of theft and retrieval, played out over an hour or so, with strategy and intrigue, humour and complaint, between them as they steal the toy from one another over and over, back and forth. Today, Arthur makes one swipe of his paw towards the toy and then abandons the whole prospect.

I offer him food. He refuses. More water. No thanks. I know then that we are near the end.

Arthur died on Sunday evening as the sun went down. He died peacefully, with Jesse, Jim and I snuggled close to him, me stroking that velvety spot between his ears as he so loved me to do. I thanked him for being my friend, my therapist, my exercise buddy and my soul-mate. I thanked him for the unconditional and unlimited love that he gave me for almost 12 years. I told him that I would always love him, and that he was a good, good boy. I told him that he could go now to that place where there is no pain and the air is always cool and the snow is always freshly fallen. And he went. And I cried.

“You went away and my heart went with you…”*

Jesse put all 112 lbs of herself into my lap and licked away the tears that were streaming down my face. Jim put his strong arms around me from behind and hugged me tight. And I love them both for it. I love them for knowing how hard it is for me to let him go, this magnificent animal who touched my soul with his, who brought me back from the edge of the abyss. This inconvenient, unmanageable, rejected puppy for whom I did not have time and did not want but could not turn away from. This wise and profound being who always gave completely of himself and made me whole again when I was broken. This animal soul who knew – and taught me — how to live fully in every moment and savour it.

Jesse and I have been walking the trails again that I used to walk with Arthur when he was young and strong and there were just the two of us. When we got Jesse, we had to limit our range because she was just a puppy and she couldn’t go as far and as long as Art could. Then the situation flipped, and although she could have made it, he was no longer up to the longer and more challenging trails.

I’m older now, too, and not as fit as I was when Arthur was in his prime, so we are taking it in stages, pushing out a little farther every day. Jesse is enjoying it immensely. Maybe someday I will be able to show her all the farthest, steepest, and roughest trails that Arthur and I explored in our adventures. Maybe for a little while, until I, too, have to go to the place where there is no pain and the air is always cool and the snow is always freshly fallen. I’m not in a hurry to get there, but Arthur, in his graceful, loving and beautiful way, has once again shown me how to do it.

*Lyrics from “You’ll Never Know” by Harry Warren & Mack Gordon, 1943.

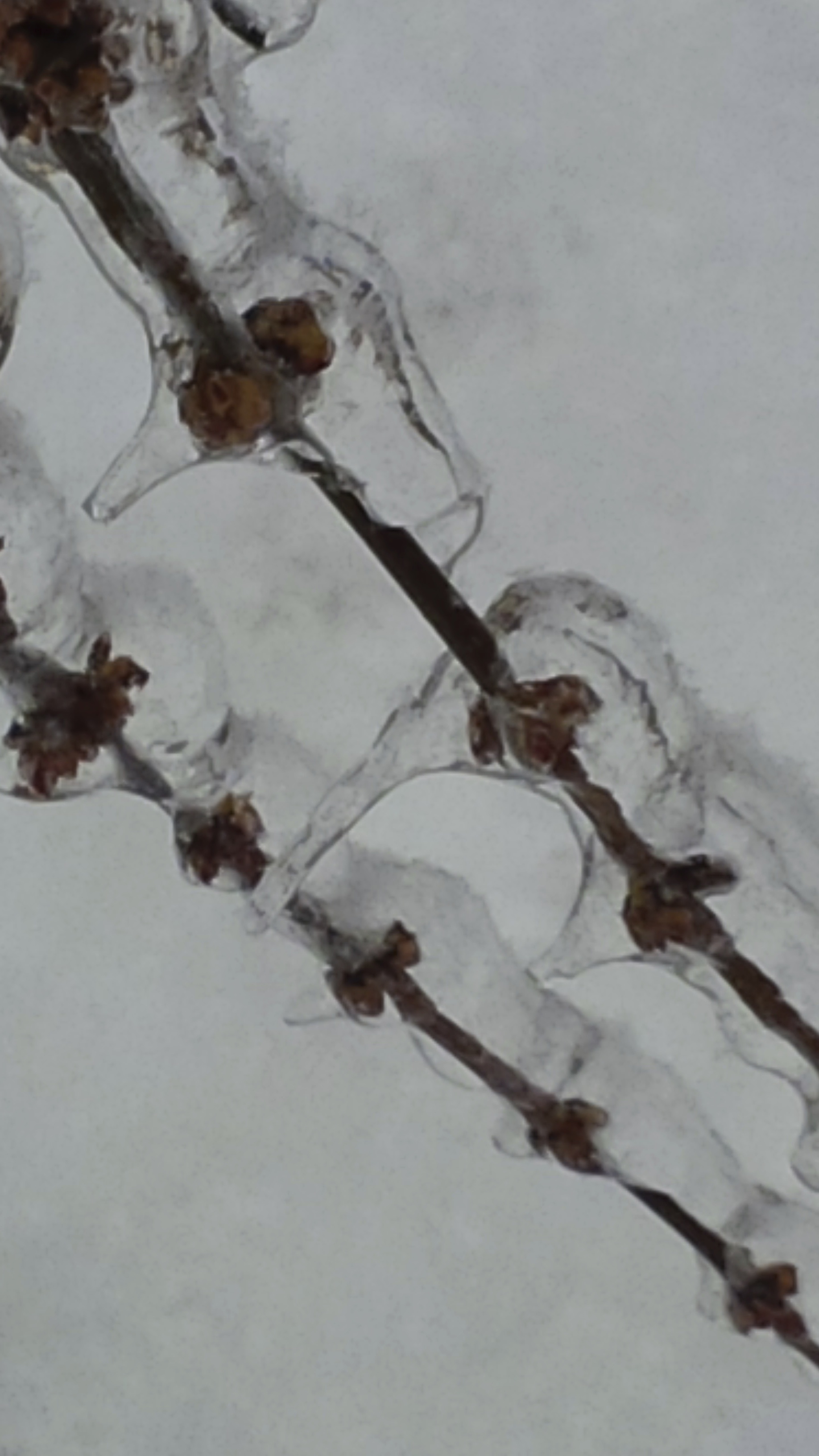

Text and photo, Copyright, Lynda Covello, 2019, all rights reserved.